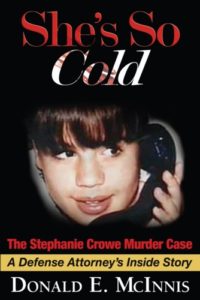

The San Diego Union-Tribune featured Donald McInnis, author of She’s So Cold: The Stephanie Crowe Murder Case — A Defense Attorney’s Inside Story, on the front page of its March 6, 2021, edition.

Haunted by the Crowe murder case, defense attorney proposes Children’s Bill of Rights

False confessions are too common when juveniles are involved, a new book argues

Written by veteran reporter John Wilkens, the story highlighted the attorney’s efforts to see his proposed Children’s Bill of Rights become law.

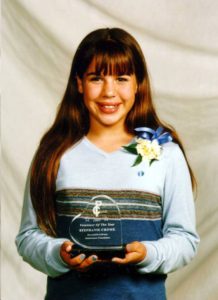

His proposal stems from a case he will never forget — the 1998 murder of 12-year-old Stephanie Crowe in Escondido, California, in 1998.

“It haunted me for years,” McInnis told the U-T. “It haunts me still.”

Officially, the knife slaying of the 12-year-old Escondido girl remains unsolved. But that’s not what troubles the 76-year-old McInnis the most.

As a defense attorney in the case, his client, one of three teenage boys originally charged and later cleared, easily could have been convicted and sent to prison, perhaps for life.

“People who think this couldn’t happen to their kids need to think again,” McInnis said.

The authors recommendations for improving the judicial system are detailed in his book, released February 11, 2021. He said he hopes to preclude the mistakes that plagued the Crowe case and drowned it in reasonable doubt, making it unlikely justice will ever be achieved for the Crowe family.

However, he believes his proposed Children’s Bill of Rights would help prevent such a scenario from happening to other juveniles. It would require, among other things, the presence of a parent or legal guardian any time a minor is questioned by police. He also wants the Miranda warning officers are required to give to suspects — You have the right to remain silent, etc. — augmented with language a child can understand.

“Studies have shown that minor children and adolescents lack the mental capability to fully comprehend the meaning of the rights,” McInnis writes. “Therefore, minors cannot make a knowing and intelligent waiver of their constitutional rights as required by law before they are interrogated.”

It’s an issue that is gathering attention in other cities amid a nationwide conversation about police reform. Sparked by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis police custody last year, much of the discussion has been about curbing alleged physical abuse. But psychological and emotional coercion are drawing scrutiny, too.

In the Bronx, N.Y., prosecutors are reviewing 31 homicide convictions that relied on confessions obtained by three detectives who worked together in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In one of their cases, a 16-year-old boy falsely confessed to killing his mother and spent 20 years in prison before he was exonerated.

Nationwide, studies have shown that false confessions, often produced by high-pressure interrogation techniques, are a leading cause of wrongful convictions in the U.S. The National Registry of Exonerations lists it as responsible for 12 percent of the 2,750 cases it has documented since 1989.

McInnis represented Aaron Houser, one of the three teenage boys charged with killing Stephanie Crowe. McInnis said he knew right away that the confessions from the other two boys, including Stephanie’s brother, Michael, would be a problem if the confessions made it in front of a jury.

“It’s so damning when a suspect says I did it, which is why police work so hard to get a confession,” McInnis said. “It’s the most powerful evidence that any prosecutor can present.”

He told the U-T he was preparing his defense of Houser to include experts who would explain why minors lack the mental capacity and life experience to understand what is happening during an interrogation. Why they are so willing to obey and please authority figures. And why they falsely confess.

Those are issues he has continued to explore through scholarly articles, including one due out soon in the Dartmouth Law Journal, Children and the Law: Time to Fulfill the Promises of Miranda and Gault.

McInnis said he decided to write the book after encountering a group of people at a senior-living facility about 12 years ago, well after the teens had been cleared in the killing and there had been widespread media coverage of it.

“They all believed the boys did it,” he said. “I remember one man telling me, ‘The cops wouldn’t have arrested them and the D.A. wouldn’t have prosecuted them if they weren’t guilty.’ That was a shocker to me.”

The book dives deeply into the interrogations of the teens, which were videotaped, and details the training and techniques detectives routinely use to obtain confessions.

McInnis said he wanted to create a record so people can better understand what happened in one of San Diego County’s most heart-wrenching judicial failures. The books title, She’s So Cold, comes from a quote by Stephanie Crowe’s mother, Cheryl, who cried it out loud while cradling her daughter’s body moments after the girl was found on the bedroom floor.

But he also wants the book to serve as a warning. There have been some changes in California law aimed at protecting minors during police questioning, he said, but problems remain. The basic interrogation methods are the same.

“While (Michael Crowe, Joshua Treadway and Aaron Houser) may never escape the images of what happened to them, I believe that we, as a society, must not close the book on this unfortunate incident,” McInnis writes. “We must remember, always, that these children might have been our own.”

To read the entire article, go to: Haunted by the Crowe murder case, defense attorney proposes Children’s Bill of Rights